As so often happens, life takes you on a detour and before you know it half a year has gone by without us showing this blog any love. For that we’re sorry. A lot of exciting stuff has happened in the art world in the meantime and my drafts folder is full of unfinished reports on events and exhibitions from the past summer that never made it onto the blog.

Let’s see if we can get this ol’ blog back on track, shall we?

It´s no secret that Kiva Gallery are big fans of Chris Pappan, so we thought it worthwhile to give a little recap on what Mr. Pappan has been up to as of late. It’s been a busy summer for Pappan. He has been involved in two big projects in his hometown Chicago. Both projects are noteworthy insofar as they allowed Pappan to work with media that are new to his practice and on a bigger scale than usual. Pappan is, of course, famous for his precise ledger drawings with a twist – they are often slightly deformed and perspectivally askew (we’ve written about that at length here). It’s exhilarating to see what happens to Pappan’s core aesthetic when he tries his hand at a new medium. Both of Pappan’s Chicago projects were developed in dialogue with the city. The first was a collaboration with The Floating Museum – a Chicago initiative that aims to turn sites of Chicago into art spaces. For this project they utilized the Green Line of the city’s transit system. The idea was that passengers could view site specific art from the train while in motion but also engage with new cultural spaces through the various stops along the line. In his contribution, Pappan collaborated with artist Monica Rickert-Bolter to construct a 25-foot inflatable sculpture entitled Founders. The sculpture consists of the heads of four non-white figures who have been of historical importance for the city of Chicago. The figures are Harold Washington – the first black mayor in any American city; Jean Baptiste DuSable – the founder of Chicago; his wife Kitihawa; and a bust by African American artist William Artis.

I think the concept of inflation is what makes the sculpture line up so neatly with Pappan´s previous preoccupation with the idea of distortion. In his ledger drawings, Pappan uses visual deformation in his depictions of sometimes stereotypical Native American imagery to suggest that what we see is a distorted truth. The meaning is conveyed by the technique he chooses. Similarly, in Founders, much conceptual weight is imparted through the very act of inflation. The stated ambition of Founders was to highlight historical figures that elevate the stories of indigenous people and people of color, honoring the often-overlooked roles they’ve had in shaping our contemporary world.

The effect and signification would not have been the same had the sculpture been executed in another medium. Consider a stone statue of the same four figures. The very medium would suggest something rigid – perhaps that the figures are eternally present to the public. However one wishes it be so, it could hardly be said to be an accurate account of their historical standing. A sculpture that has to be inflated, on the other hand, conveys that it takes an effort for it to get into public view. Moreover, it lends an air of impermanence and fragility to the sculpture that underscores how easily non-white people fall out of historical view.

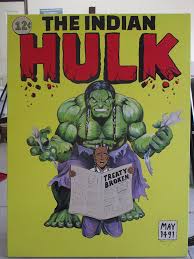

Pappan’s other Chicago-specific project was conceived within the frame of Expo Chicago – an art event taking place in September each year. A part of Expo consisted of Override – a project that let artists take over billboards throughout the city. Pappan’s contribution was Ghost of Route 66 – an image of three central Native American figures wrapped in blankets, flanked by two outlined (ghostly) repetitions of the central figures.

The large image looks completely awesome against the backdrop of Chicago’s high-rises and office buildings. But taking into account the large, commercial format of a billboard, it feels inadequate to dismiss the image with an Instagram-friendly “awesome!”.

Seeing three stoic Native Americans within a space usually reserved for the purpose of advertising goods and services to be sold is an emotionally complex experience. This complexity has always been Pappan’s “hook” and what sets him apart – things are never quite what they seem; there are dimensions and layers; subtexts and buried meanings.

These most recent works of Pappan bring forth the complexity in a triumphant new scale and we hope to see more of it.

figurative content, which is the expected source of suspense considering there is a gun involved, tension and drama is here conveyed primarily through paint. Unlike other paintings by Romero, there is a strict, almost dichotomous, protocol to the distribution of paint that tells it’s own wordless story. The totality of the background, or the field that surrounds the figure, is made up entirely of horizontal brushstrokes. This strict painterly scheme is however contrasted sharply by the formless spatter of paint spread across the center of the painting particularly and out toward the edges of the canvas. Control and abandonment here lives side by side and is through paint brought to bear upon the figurative content in a way that gives it added depth. The established tension tells of a threat of violent eruption that seems to belie the cool posture and demeanour of the girl holding the gun.

figurative content, which is the expected source of suspense considering there is a gun involved, tension and drama is here conveyed primarily through paint. Unlike other paintings by Romero, there is a strict, almost dichotomous, protocol to the distribution of paint that tells it’s own wordless story. The totality of the background, or the field that surrounds the figure, is made up entirely of horizontal brushstrokes. This strict painterly scheme is however contrasted sharply by the formless spatter of paint spread across the center of the painting particularly and out toward the edges of the canvas. Control and abandonment here lives side by side and is through paint brought to bear upon the figurative content in a way that gives it added depth. The established tension tells of a threat of violent eruption that seems to belie the cool posture and demeanour of the girl holding the gun.