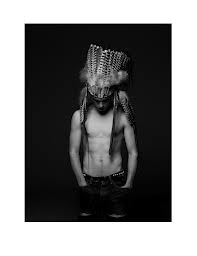

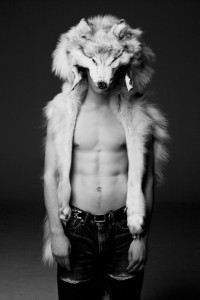

Traditional Native American headdresses have been popping up in all kinds of inappropriate places as of late. Last year alone saw a scantily clad model sporting a war bonnet at Victoria Secret’s annual runway extravaganza, a distasteful No Doubt video, a flat out racist release party for clothing label Paul Frank themed around powwows that involved play-acted scalpings, tomahawks and feathered dress-up, to mention but a selection of cases that went beyond the norms of cultural respect. These events sparked uproars on blogs and in other media, resulting in apologies from all the offending parties. The fashion industry, however, seems to have missed out on the larger lesson as traditional Indian attributes continue to hold appeal for fashion designers less discerning on questions of cultural integrity. One particular blatant example that seems to have passed the radar of most commentators is the Japanese label Neighborhood. The lookbook for its spring/summer 2013 collection features white models wearing prominent feathered headdresses along with other Native American references.

Traditional Native American headdresses have been popping up in all kinds of inappropriate places as of late. Last year alone saw a scantily clad model sporting a war bonnet at Victoria Secret’s annual runway extravaganza, a distasteful No Doubt video, a flat out racist release party for clothing label Paul Frank themed around powwows that involved play-acted scalpings, tomahawks and feathered dress-up, to mention but a selection of cases that went beyond the norms of cultural respect. These events sparked uproars on blogs and in other media, resulting in apologies from all the offending parties. The fashion industry, however, seems to have missed out on the larger lesson as traditional Indian attributes continue to hold appeal for fashion designers less discerning on questions of cultural integrity. One particular blatant example that seems to have passed the radar of most commentators is the Japanese label Neighborhood. The lookbook for its spring/summer 2013 collection features white models wearing prominent feathered headdresses along with other Native American references.

One reason that this case has escaped the attention of sites such as Native Appropriations, Beyond Buckskin and other blogs that are usually hyper-alert to questions of this matter could be that the label is not widely distributed outside of Japan. Yet Neighborhood is not completely unavailable on western shores. It is sold in hip online stores such as Mr Porter and Tres Bien shop. On top of this, and due to the use of exclusively western-looking white models, the campaign is arguably addressed to a western clientele which makes it fair to say that there is a certain ”hipster headdress” tendency at work here.

Now, Neighborhood belongs to a niche of Japanese designer labels – Kapital and Real McCoy are some others – that are obsessed with Americana and the historical garments of America’s past. In these labels quests for authenticity, historical accuracy matters down to the smallest stitch. Such sartorial reverence does of course not grant them a free pass to play fast and loose with loaded spiritual symbols of other cultures. It does, however, suggest that at least some thought has gone into the creative process. But just what kind of thought are we dealing with? Chasing after intent is of course often a dead end in these matters as most cultural appropriators will attest to their well-meaning. So let’s proceed from what we have – the photos. They are undeniably beautiful and in comparison to the other photos in the lookbook the Indian themed ones seem to convey a different mood. The model turns down his head in what appears to be solemn introspection. This is a welcome departure from the reigning visual tropes involving Native headdress – the sexy Indian and the proud warrior. Were these art photos they might be interpreted as propositions of the white man’s guilt or at the very least as showing signs of humility. But these are not images of art. Even supposing that the premises were of critical nature, the message is betrayed by the specific context, the purpose of which is to market clothes. What clothes, one might ask considering that there is little evidence of the label’s actual designs to be seen in these photos, presuming of course that the headdress is not part of the collection. A closer look on one of the photos will however reveal something just below the model’s unclothed torso that actually is part of the collection. It is the Thunderbird belt, a beaded belt inspired by traditional Native American craftmanship. The point of the headdress is in other words to reinforce the impression of Indian authenticity. Exactly how a white person serves this purpose is unclear, and extremely problematic.

Now, Neighborhood belongs to a niche of Japanese designer labels – Kapital and Real McCoy are some others – that are obsessed with Americana and the historical garments of America’s past. In these labels quests for authenticity, historical accuracy matters down to the smallest stitch. Such sartorial reverence does of course not grant them a free pass to play fast and loose with loaded spiritual symbols of other cultures. It does, however, suggest that at least some thought has gone into the creative process. But just what kind of thought are we dealing with? Chasing after intent is of course often a dead end in these matters as most cultural appropriators will attest to their well-meaning. So let’s proceed from what we have – the photos. They are undeniably beautiful and in comparison to the other photos in the lookbook the Indian themed ones seem to convey a different mood. The model turns down his head in what appears to be solemn introspection. This is a welcome departure from the reigning visual tropes involving Native headdress – the sexy Indian and the proud warrior. Were these art photos they might be interpreted as propositions of the white man’s guilt or at the very least as showing signs of humility. But these are not images of art. Even supposing that the premises were of critical nature, the message is betrayed by the specific context, the purpose of which is to market clothes. What clothes, one might ask considering that there is little evidence of the label’s actual designs to be seen in these photos, presuming of course that the headdress is not part of the collection. A closer look on one of the photos will however reveal something just below the model’s unclothed torso that actually is part of the collection. It is the Thunderbird belt, a beaded belt inspired by traditional Native American craftmanship. The point of the headdress is in other words to reinforce the impression of Indian authenticity. Exactly how a white person serves this purpose is unclear, and extremely problematic.

I myself am a white person of Swedish origin. As a collector of Native American art I have a deep love for the aesthetics and traditions of cultures I am not born into. It is my hope that my passion can be practiced without infringing upon the meaning and symbolic significance that Native cultures ascribe to their objects. I understand that certain objects are sacred and require reverence and understanding at a level beyond mere aesthetic appreciation. One such item is the ceremonial headdress.

As Jennifer Weston (Hunkpapa Lakota, Standing Rock Sioux) explains on the blog Jezebel: ”While ceremonies varied among the diverse plains tribes who produced these headdresses, most involved specific prayers and actions, often relating to EACH single feather. Honor songs and ceremonies, for men and women warriors, come from our languages and represent ancient spiritual practices deeply tied to tribal homelands and their biodiversity.”

As Jennifer Weston (Hunkpapa Lakota, Standing Rock Sioux) explains on the blog Jezebel: ”While ceremonies varied among the diverse plains tribes who produced these headdresses, most involved specific prayers and actions, often relating to EACH single feather. Honor songs and ceremonies, for men and women warriors, come from our languages and represent ancient spiritual practices deeply tied to tribal homelands and their biodiversity.”

To therefore use headdress as shorthand for Native American authenticity is not only reductive and stereotypical but deeply disrespectful to the traditions they are trying to pay hommage to. Sure, the photos look cool and all. But just as you can’t use crosses and other religious symbols without being expected to supply an explanation as to their spiritual significance, it shouldn’t be conceivable to engage with headdress in a manner that stops at mere superficial admiration. That’s how easy appreciation can turn to affront. If only Neighborhood would apply as much care and respect to symbolic matters as they do to the construction of their clothes such self-undermining blunders of appropriation could be avoided.